AMMs are at the core of several of DeFi’s most popular protocols and apps. If you’ve used Uniswap or Curve, for example, you’ve used an AMM. They’re decentralised trading pools that let you provide liquidity directly to markets when you buy and sell cryptocurrencies.

In crypto, decentralised exchanges (‘DEXes’) are the first sector to utilise AMMs. Before AMM-based DEXes, if you wanted to trade a token, you had to wait for a CEX to list it. Growing adoption of AMM platforms is slowly decentralising token issuance and listing processes. Today, AMMs are consistently among the first venues where a given token can be bought or sold.

AMMs are challenging a decades-long era where markets are made through centralised order books, with evidence suggesting on-chain orderbook systems are at a disadvantage relative to on-chain AMM systems.[1]

“[AMMs] are smart contracts that create a liquidity pool of ERC-20 tokens (or tokens that adhere to a similar standard on another blockchain), which are automatically traded by an algorithm rather than an order book. This effectively replaces a traditional limit order-book with a system where assets can be automatically swapped against the pool’s latest price.”[5]

Breaking Down the Acronym

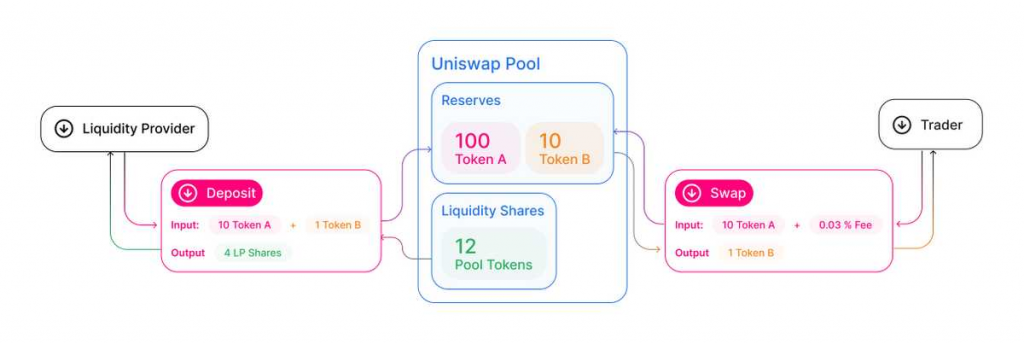

The ‘automated’ part of ‘automated market maker’ just means that AMMs are algorithmic agents that perform those functions and, as a result, provide liquidity in a market.[4] Smart contracts serve as the custodian of funds, with liquidity providers (‘LPs’) receiving tokens (‘LP tokens’) that represent proportionate ownership of a given liquidity pool. The smart contracts hold liquidity reserves of various tokens, and trades are executed directly against these reserves.

As for the ‘market maker’ part, it refers to the fact that AMMs make markets. That is, they help facilitate trading of assets. To transact tokens on an exchange with other investors requires underlying assets to be present to execute the trade so when someone sells 10 ETH for 30,000 USDC, there is 30,000 USDC on the exchange for the seller to receive. Many financial institutions offer the service of ‘making a market’ for particular financial assets.

In DeFi, basically anyone can create a market by depositing tokens into a smart contract. People can immediately trade against this smart contract, which automates the pricing, the price updating and the rebalancing.

Pricing for Liquidity Pools of an AMM

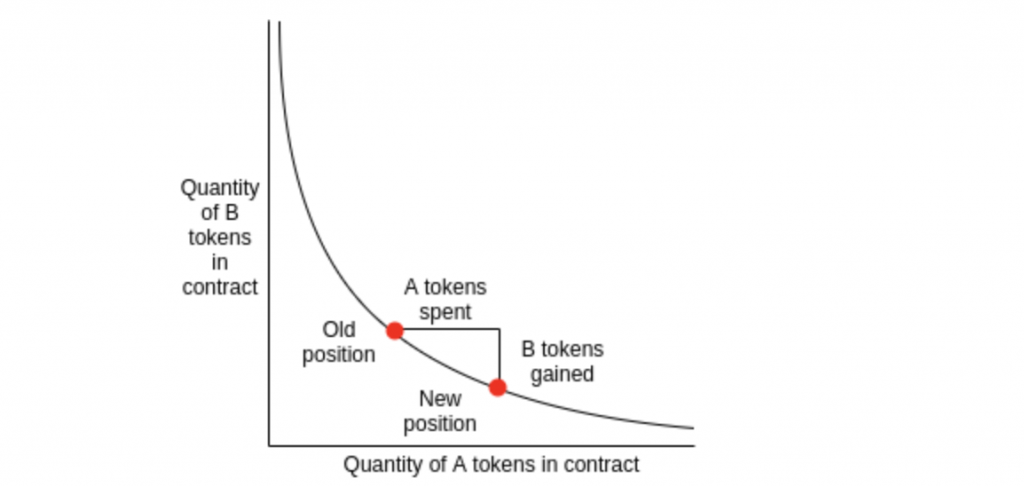

AMM liquidity pool prices are automatically determined using various mechanisms. The most popular is the ‘constant product market maker’ mechanism—often called the ‘constant function market maker’ (‘CFMM’)—that has the simplified formula, x*y=k, where ‘x’ and ‘y’ are the reserves of each asset. “The term “constant function” refers to the fact that any trade must change the reserves in such a way that the product of those reserves remains unchanged (i.e. equal to a constant).” [4]

CFMMs define a relationship between 2 or more tokens. The exchange contracts for 2-asset liquidity pools each hold a reserve of the blockchain’s native token (ETH for Ethereum, MATIC for Polygon) and associated altcoin (ERC-20 for Ethereum, BEP-20 for BSC). The blockchain’s native tokens like ETH are used as a bridge currency, as each liquidity pool has a portion of the native token in the ETH/XYZ pair.

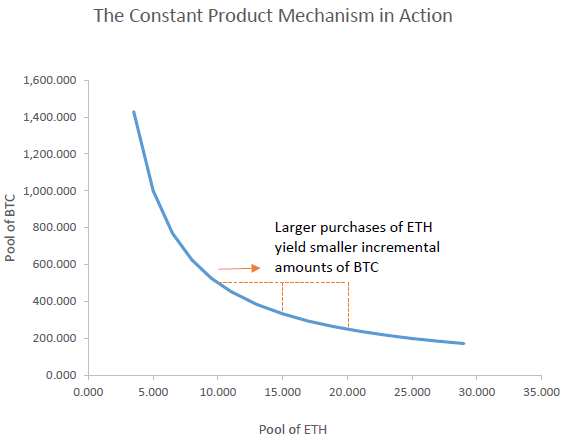

Below is a visualisation of the x*y=k formula. CFMM liquidity pool with the 2 assets, wBTC & ETH in the wBTC–ETH LP pool.

As trades are made using the liquidity pool reserves, prices dynamically move along the price curve in order for the contract to always maintain the invariant that x*y=k for some constant ‘k’. (Note that AMMs do not update price as other markets move. Instead, price moves as the reserve ratio of the tokens in the pool updates, which happens after each trade.)

AMM Participants

- LPs: A liquidity pool in an AMM DEX is created by a ‘liquidity pool creator’ who deploys the underlying smart contract that acts as a liquidity pool with some initial supply assets. Additional parties can deposit assets into the smart contract and receive LP tokens proportionate to their liquidity contribution as a fraction of the entire pool.

- Divergence loss: For LPs, assets supplied to a protocol are still exposed to volatility risk, which comes into play in addition to the loss of time value of locked funds.

- User (traders/swappers): Traders submit swap orders to the liquidity pool, and the smart contract automatically calculates the exchange rate based on the conservation function before executing the exchange order accordingly. The user pays a small fee, which goes to LPs.

- Slippage: The difference between the spot price and the realised price of a trade and is caused by the AMM’s curve design that dictates the asset prices.

- Arbitrageurs: Market participants who compare asset prices across many CEXes and DEXes and execute trades based on price gaps to extract profit risk-freely.

- Protocol team: AMM-based DEXes have core development teams who guide the decentralised organisation in the expansion of their market making.

History of AMMs

A brief history of AMMs used in the crypto space:

- Bancor (2017): Introduced on-chain AMMs.

- Uniswap (2018): The first AMM that achieved meaningful volumes and kickstarted the AMM wave in DeFi.

- Kyber (2018): Private automated liquidity pools.

- Curve (2019): The first AMM optimised for trades among stablecoins and other similarly priced synthetic assets.

- Balancer (2020): The first AMM to enable liquidity pool creators to customise weights between 2–8 assets in the single pool.

- Bancor V2 (2020): The first AMM to introduce dynamic weights for liquidity pools by realizing the losses by Bancor LPs to mitigate impermanent loss. V2 also introduced single-sided exposure, allowing investors to deposit one asset into a 2-asset liquidity pool, and creating the concept of impermanent loss insurance.

- Blackholeswap (2020): The first AMM that can process transactions exceeding its existing liquidity by tapping into the excess supply on Compound or other lending protocols.[2]

AMMs vs CEXes

If you’ve used a CEX with an order book you’d be familiar with the way they work compared to an AMM. CEXes use an order book to simply compile all orders sent to the exchange, placing 2 sides: the buy order and sell orders. These are limit orders that someone has set (makers) and will sit there until it’s executed (takers). Compared to CEXes, AMMs have the advantages of decentralisation, automation and continuous liquidity.

In total, AMMs have risen steadily. According to CoinGecko, AMMs have a total market cap of ~$35B, with a daily trading volume ~$6M. Underscoring Uniswap’s dominance among AMMs, it alone accounts for ~$1.5B of trading volume.

Below are examples of AMMs built on non-Ethereum blockchains:

- Raydium (Solana)

- PancakeSwap (BSC)

- Pangolin (Avalanche)

- QuickSwap (Polygon)

- SpookySwap (Fantom)

- Serum (Solana)

Whilst usage of AMMs in crypto has grown significantly in recent years, the vast majority of trading volume still goes through traditional order books of CEXes like Binance and Coinbase.

Further Reading

- Constant Function Market Makers: DeFi’s “Zero to One” Innovation

- A Deep Dive into our Virtual AMM (vAMM)

- Citadel’s Sharpe is Uniswap’s Opportunity

- Improved Price Oracles: Constant Function Market Makers [PDF]

- An analysis of Uniswap markets [PDF]

- Survey of AMM Algorithms

- Balancer whitepaper

- Automated Market Making: Theory and Practice [PDF]

Sources

1 DODO: A Revolution in On-Chain Liquidity

2 36-tweet thread by @0xminion

3 A Deep Dive into our Virtual AMM

4 CFMM: DeFi’s “Zero to One” Innovation

5 DeFi Explained: AMMs

6 SoK: DEX with AMM [PDF]