You’ll see crypto-assets or organisations claiming to be ‘decentralised’—but what does this mean, and are your crypto-assets genuinely decentralised? ‘Decentralisation’ can be a misnomer and used wrongfully—in many cases, crypto networks or crypto-assets are not entirely decentralised.

We dive into how to think about decentralisation and how it’s more of a spectrum than a fixed-end state.

Contents

Summary

- Decentralisation of blockchain platforms or decentralised applications (dapps) is a spectrum—some more decentralised than others, and there is no agreed final state.

- Decentralisation can depend on whether your crypto is proof of work (PoW) or proof of stake (PoS).

- The focus with PoS is the distribution of coins, circulating supply staked and how many validators.

- For PoW systems, it’s the size of their cumulative hash rate and the number of node operators.

- However, there are many other determinants when judging the decentralisation spectrum:

- Who runs the network, and how distributed is it?

- Who owns and controls the coins?

- Who makes the decisions?

- Is there a central team behind it?

- Is it accessible to run or participate in the network?

- Does the chain or dApp have emergency powers?

- Decentralisation matters because:

- More decentralised systems are less prone to network attacks and have better security guarantees.

- Higher centralisation can mean a higher risk of malicious community members taking control or exploiting the dApp.

- Less decentralised systems could fall victim to regulatory capture.

- Overcoming decentralisation:

- Centralisation is often needed early on.

- There could be a plan to decentralise over time—there’s a movement to install ‘safe harbour’ laws to overcome this grey area.

- There have been many examples of centralisations exploited by rogue attackers:

- Attacks on multi-signature (multi-sig) wallets or validators (Ronin Blockchain)

- Governance attacks (Beanstalk)

- High emergency powers and unfair governance (Solend)

What Does ‘Decentralisation’ Even Mean?

In its simplest form, decentralisation refers to a process by which an organisation transfers planning and control from a centralised entity.

In blockchain and cryptocurrency, this means transferring the process of maintaining the blockchain or control of crypto-based applications (dapps) away from a central few to a distributed network where no single entity has total control.

Decentralised networks strive to reduce the trust participants must place in one another or a single entity’s ability to exert authority or control.

Decentralisation as a Spectrum

It’s increasingly difficult to label blockchains or dapps as either decentralised or not.

No simple point can officially label where decentralisation is achieved; it’s more of a spectrum versus a linear end state.

Example: Amazon Web Services are not decentralised, as its web of servers is centrally controlled via Amazon. Suppose it wants to shut down an application; it can. The same can be applied to many crypto-assets or platforms that still have central control over the network or dapp. Whereas the Bitcoin network is agreed to be highly decentralised, it doesn’t rely on a single actor or group of people to support the network, nor can a single entity shut down an application or transaction on it. It’s distributed among cryptocurrency miners worldwide—one miner cannot simply take control of the network on their own.

The spectrum

Every blockchain, decentralised application (dapp), decentralised autonomous organisation (DAO), or related blockchain solution adopts varying levels of decentralisation.

However, it can be very confusing for everyday people to understand what ‘decentralisation’ means. And unfortunately can be misused when the application or platform may be highly centralised.

Often, these projects aim to be decentralised but are not currently.

So decentralisation is best thought of as a spectrum. Some platforms are further down the decentralisation scale than others, and some may start very centralised to hand over ‘control’ to a community.

Bitcoin’s widely agreed to be the most decentralised crypto asset and network—due to many factors:

- Bitcoin has no CEO, public founder or foundation.

- There was no pre-crypto deal or allocation for insiders: BTC was mined organically from inception.

- BTC traded for years with little value and has been around for 10+ years.

- Survived many significant changes—most recently a China mining ban.

- The Bitcoin network is widely distributed with no single miner or actor who can censor transactions or make protocol-level changes easily (requires significant community discussion for big changes, which often takes years).

Factors to Determine Decentralisation

Now we understand decentralisation is a spectrum and end goal, we can consider the different factors when judging how ‘decentralised’ your crypto-asset or blockchain is.

We can think about decentralisation by asking essential questions about who runs the network, who holds the coins and who makes the decisions.

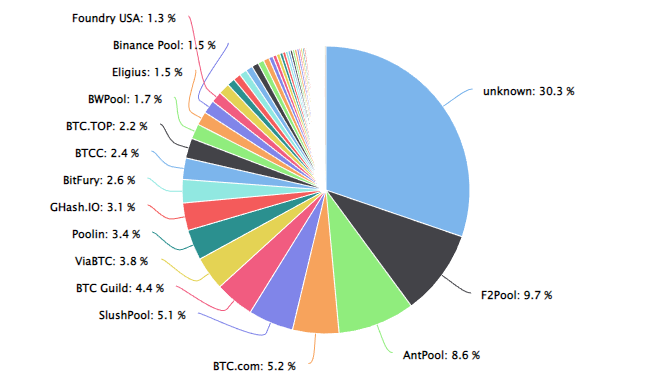

Proof-of-work blockchains—who controls the hash rate? The decentralisation and security of these networks primarily depend on how high the hash rate is and how many entities participate. The hash rate = the cumulative processing power miners provide the network: higher the hash rate = the harder to disrupt.

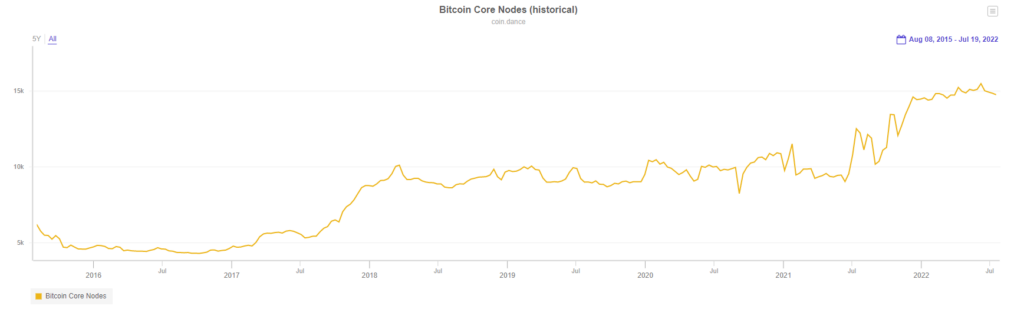

- Currently, there are ~15K nodes—although node count is expected to be an under-representation due to many being private.

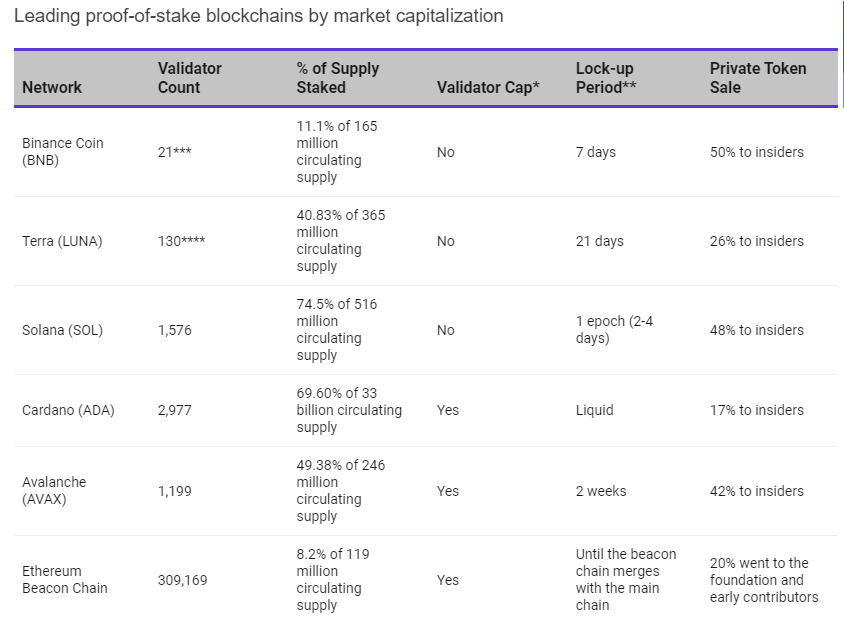

Proof-of-stake blockchains depend on the count of stake pools or validators: The most common and critical decentralisation aspect. How many validators (validators operate the same as miners in PoS) are there processing transactions?

- Is the network run by only a handful of miners/validators and distributed across many timezones, geography and groups.

- Limited validators could indicate a less diverse range of operators processing transactions, potentially increasing centralisation if some are concerned or go down.

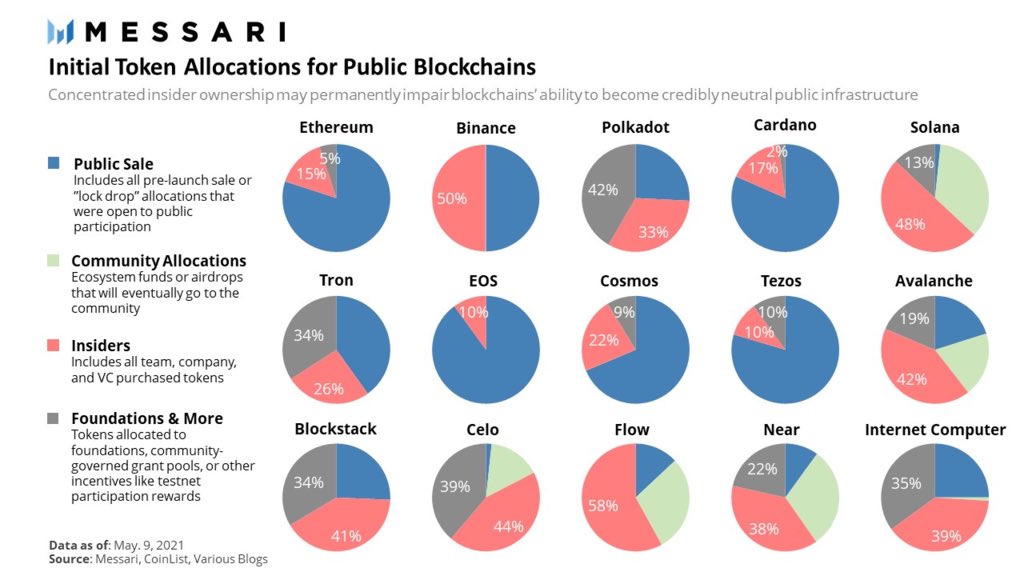

Who controls the supply? In PoS systems, token supply matters more—as a greater stake (network token) means more influence over the underlying application. If insiders had or control a majority of the crypto-asset, this could also reduce total decentralisation. As per the below screenshot, Messari calculated the high level of insider tokens towards public blockchains as of May 2021.

Is there a central team behind it? If a group of insiders runs the crypto-asset, a CEO or foundation, this could point to increased levels of centralisation.

- Bitcoin has no team, CEO or company. There is no one person behind or developers in charge of a roadmap.

- Ethereum has no CEO but does have the Ethereum Foundation and a group of engineers assisting in developing the protocol. However, these teams and people building it are wide and distributed.

- Solana has heavy development by Solana Labs and the community.

- DeFi dapps like 1inch or Uniswap will have foundations or a team behind them driving the application forward (1inch Foundation or Uniswap Labs).

Figureheads: Some platforms can have a central leader with influence over a network or platform through public discourse, which can lead to levels of centralisation.

- Such as Vitalik Buterin (Ethereum), C.Z. (Binance), Charles Hoskinson (Cardano) or Do Kwon (Terra).

Can the chain be “turned off/reset”? Some blockchains have experienced network issues. In September 2021, Solana validators grouped to reset the chain via Discord chat due to significant network issues. Having a group of validators able to stop the blockchain means they have extreme control.

Governance: who makes the decision? How are decisions made? If one party can unilaterally control decision-making, it points to higher degrees of centralisation.

- A trade-off exits because centralised governance is often needed at the start of a project’s life cycle.

- However, if someone owns a majority of the coins, they can hijack governance to pass proposals against majority rule.

Does the chain or dapp have ’emergency powers’? Users may not know blockchain or dapp creators may have emergency powers or a ‘back door’ to change the state of the network in case of a fatal bug. If a team can exert emergency powers over the blockchain or dapp this points to significant centralisation.

- Like governance, these powers can be required early on and removed later.

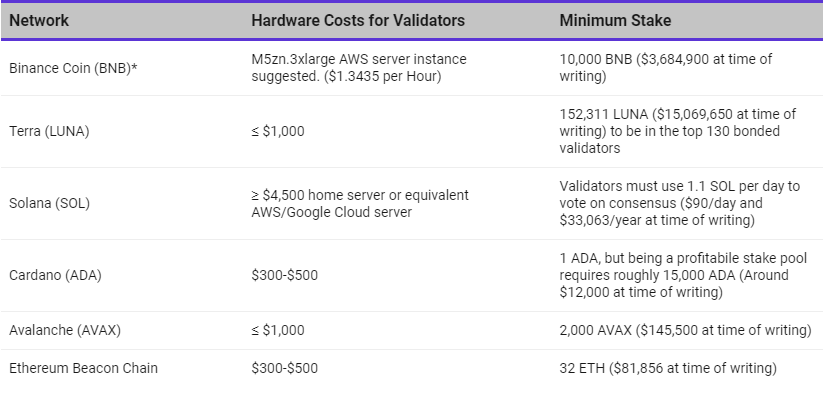

Accessibility: How easy is it to run or participate in the network? Originally bitcoin was open and accessible to anyone, but as miner difficulty increases, it requires more expensive equipment to be profitable. PoS networks need both hardware costs and a minimum stake which can increase barriers to entry.

- Higher cost to participate = less diversity to participate in running the network, risking end up centralised due to high barriers to entry.

Why Does It Matter?

As blockchains become less niche and widely used, so does the total value locked and the importance of information held on these networks. Increasing the motivation for individuals to exploit the centralisations of these blockchain networks or dapps—for example, by Nation States.

Decentralsiaiton is important, due to:

- Important to censorship resistance—more decentralised systems are less prone to network attacks and have higher security.

- Less decentralised systems could fall victim to regulatory capture.

- Fewer conflicts of interest—more transparency.

- Cannot enact changes unless the majority of participating parties agree.

- Higher centralisation = higher risk of malicious community members taking control or exploiting the dapp.

Trial of Bits study ‘Are Blockchains Decentralised?

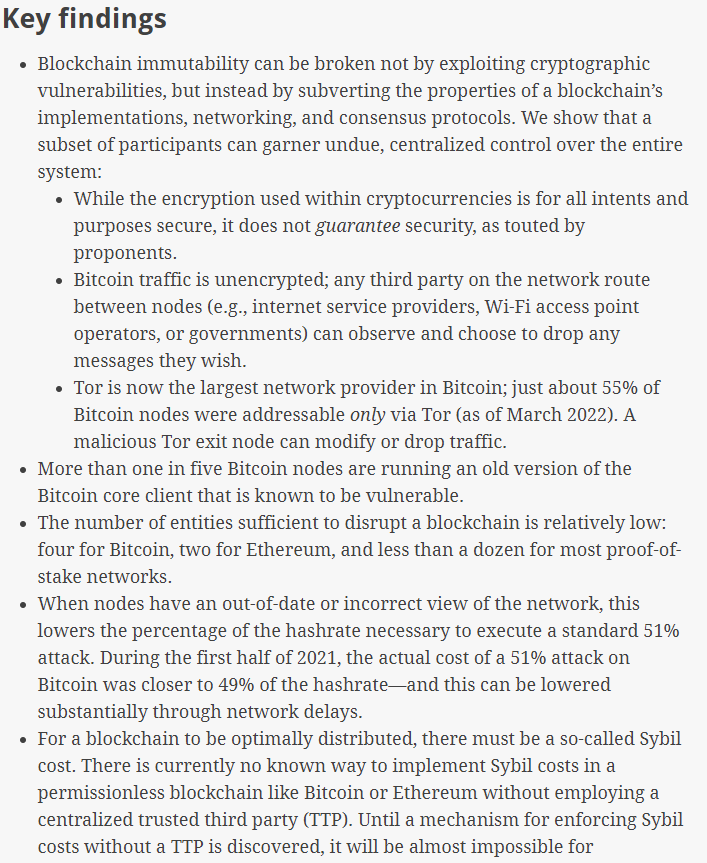

Software security research company Trail of Bits conducted a 2022 study for the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) into whether or not blockchains are decentralised. They concluded:

- Current blockchains such as Bitcoin and Ethereum have unintended centralisations that pose a risk.

- Think of these unintended centralisations as ways external actors can make the blockchain work in a way other than you’d expect.

- Questions immutability “not by exploiting cryptographic vulnerabilities but instead by subverting the properties of a blockchain’s implementations, networking, and consensus protocols.”

- These risks are not discussed with users of blockchains.

- Unintended centralisations include risks such as the power of nation states to control internet service providers (ISPs) or influence blockchains.

- A call for the industry to recognise these risks to improve security practices.

Overcoming Decentralisation

Just because the crypto-organisation is centralised or has centralisation features may not mean the project is “bad” or “doomed”.

- Newer blockchains will rely on centralised development teams, with some aiming to decentralise this process over time; this may be in the form of:

- More validators

- Forms of community governance

- Releasing the platform as open-source

- Adding more developers.

- Centralisation at the start is needed: if there’s a massive bug, the team needs to fix it quickly and upgrade the protocol.

- There is an ongoing debate about ‘how much decentralisation is enough’.

- SEC Commissioner Hester M. Peirce proposed a ‘safe harbour‘ framework to provide developers with a 3-year grace period they can facilitate participation in and the development of a functional or decentralised network.

Examples of Centralisation Gone Bad

Applying what we’ve learnt in this resource, we can show real-life examples in the ecosystem where ‘decentralised’ platforms were shown to be highly centralised, causing significant problems.

Solend: Solend claimed to be a “decentralised lending and borrowing protocol”, however, used emergency powers and an unfairly weighted vote to take control of a user’s funds locked in the platform.

The governance process was highly centralised as one user had 90% of the voting power—meaning they could push through decisions even if most people disagreed. The ability for a decentralised protocol to take control of users’ funds locked in the platform is also highly centralised. Although it didn’t pass due to community backlash, it shows what they could do.

Problem: High emergency powers and unfair governance.

Beanstalk: A DeFi protocol on Ethereum that lost $182M due to a cyber attack on the platform. Essentially the attackers borrowed funds to buy the platform’s native token. Once they had majority voting power, they could change the protocol, and quickly passed a malicious governance proposal to drain all the protocol funds into a private Ethereum wallet.

Problem: Governance attack.

Ronin Blockchain: In March 2022, Ronin was exploited for $625M in an attack that U.S. officials have linked to North Korea.

The attack was due to the highly centralised nature of the Ronin blockchain where attackers used a sophisticated phishing attack to take control of private keys to validator nodes resulting in the compromise of five validator nodes—the threshold required to approve a transaction.

Problem: Validator attack on multi-sig wallet.